Children's Horror and the New Pulp

So Late-Stage Capitalism, Pulp Horror, and YouTube Walk Into a Pizzaria...

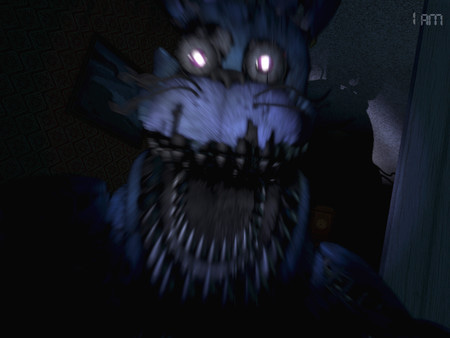

On August 8th, 2014, a man by the name of Scott Cawthon independently published his solodev game Five Nights at Freddy’s (FNaF).

Just a few days later on August 12th, 2014, a man by the name of Mark “Markiplier” Fischbach would upload a video of himself playing the pizza-adjacent horror game onto YouTube, calling it “the scariest game in years.”

The world was, quite frankly, never the same.

The Rise of “Mascot Horror”

The term “mascot horror” has disputed origins. Some believe the term derives from Five Nights at Freddy’s, wherein the enemies are animatronics akin to sports team mascots. Others, however, say that it likely refers to the greater trend of indie horror games being associated with a primary “mascot” of a character, which then becomes an ad-hoc representation of the game itself: think Freddy Fazbear, Huggy Wuggy, Bendy… those sorts of guys. Even if you don’t know their names, I’d bet you’ve seen their “faces.”

Regardless of the name’s origins, mascot horror as a subgenre absolutely exploded in the second half of the 2010s and continues to be immensely popular today - specifically in the indie game space. But what exactly does this genre entail? And why is it so enticing?

Common themes and characteristics of mascot horror:

“Kiddish” aesthetics:

Bright colors, toys, friendly/familiar themes and settings which are then subverted for the purpose of a scare. This works on children because of its uncanniness and subversion of the familiar, while simultaneously working on adults by upending the nostalgia factor and returning the player to a smaller, more vulnerable chapter of their lives. A great example of this is My Friendly Neighborhood, an indie title published by DreadXP, wherein the enemies and environment are a hostile version of the types of puppets and sets you might find on a children’s educational television show, such as Sesame Street.

Serialized format:

Most of these games are released as part of a series - whether individual installments (such as Five Nights at Freddy’s, which is currently at 10 games and counting) or in a chapter format of a singular story, such as in Poppy Playtime, from MOB Games, which currently has two chapters and is awaiting a third. Like FNaF, Poppy Playtime uses their various installments to introduce new characters/enemies and mechanics to keep things fresh and provide iteration upon the genre’s typically simplistic gameplay.

Scares are often jumpscare or chase-sequence based:

Very little blood or gore is depicted due to the target audience being children (and thus keeping that ESRB rating low).

Simple puzzles:

Puzzles are simple and developmentally appropriate for grade-school children. An example of this would be the pilotable drone in Garten of Banban. The player must use a remote control drone to press various buttons in order to open doors. Why this is a feature of a kindergarten/daycare center? Anyone’s guess.

Gameplay mechanics may be more sophisticated depending on the title, but are ultimately still approachable for players of all ages.

Nebulous metanarrative:

These games are well known for being narratively confusing. With continuous retcons, “lore” (often hidden), timelines, and sometimes accompanying alternate reality games (ARGs), we can assume that this particular feature is derived from a need for continuous engagement, rather than a genuine interest in nonlinear narrative structures - but I digress. A classic example of this is the game Hello Neighbor from tinyBuild, wherein a nosy neighborhood child is trying to figure out what their eccentric neighbor has locked in their basement. The narrative of this game is as wild as it is confusing, leaving many players to question if they were merely making it up as they went.

Virality:

These indie-horror games are not marketed with flashy PR campaigns or publisher press releases - instead they are made popular by harnessing the power of internet virality.

…That last one is a biggie. In fact, it’s widely speculated by horror fans that mascot horror would never have reached its fever pitch in the last couple of years if it hadn’t been for one compounding meteoric rise: “let’s play” and gaming YouTubers. In these YouTube videos, gaming personalities would record themselves playing the scary game and showcase their terrified reactions. And viewers? Ate. It. Up.

YouTuber Lanza in his video essay Poppy Playtime and the Ever-Growing Problem with Horror Games for Kids summarizes the symbiotic relationship let’s play-ers and game developers have in this subgenre:

“Let’s play-ers play the game - game gets popular - Game Theory [an (in)famous channel on YouTube] makes a video going over the deeper lore - game gets even more popular… and this is 100% free advertising that the game developers don’t have to pay a single cent for. All they have to do is get their game noticed by the right people, and theoretically the money should start pouring in.”

- Lanza, Poppy Playtime and the Ever-Growing Problem with Horror Games For Kids

This mutualistic relationship catapulted mascot horror to popularity: the game developers sell copies and the let’s players get views and that sweet, sweet ad revenue. It’s a win-win! But it doesn’t stop there - developers and YouTubers alike often openly encourage and foster online fandoms of their content. This leads to things like fanart, fan theories, and even entire fan-games. This drives continued engagement: more clicks, more views, and more outreach, meaning that they can almost guarantee a greater player-base should they release a subsequent installment. In the world of mascot horror: more is always better.

And this hasn’t gone unnoticed, as many indie developers are increasingly interested in the subgenre and out for their piece of the (pizza) pie.

Some titles associated with the genre are:

…The list honestly goes on, and there are cases to be made for inclusion or exclusion for any of the above (and those not mentioned here).

Even if you aren’t familiar with any of these games, a quick glance at their Steam pages can give you an idea of how they are thematically coherent. They’re aesthetically stylized, short-form, meant for quick, cheap, enjoyable scares and entertainment before being readily discarded for the next one that comes out in the next few months.

In short: mascot horror is a new form of pulp.

What’s Pulp, Anyway?

“Pulp” as a genre originated from “pulp magazines” (sometimes referred to historically as “the pulps”). The Pulp Magazines Project, an open-source archive of all things pulp, credits the birth of the genre in the 1890s to a convergence of several cultural phenomena, including a readily increasing literacy rate, establishment of a working class with pocket change to burn, and the rise of American news and magazine culture.

Pulp magazines, which were typically associated with genre fiction (such as true crime, horror, or erotica), were on the cheaper side of most newsstand offerings. This meant that they had to be dirt cheap to produce in order to make a profit. So rather than print them on decent paper, they were instead printed on paper made almost entirely out of wood pulp: ultimately earning the genre its name.

Picture the absolute poorest-grade toilet paper you can imagine: the kind you might find at a public school (or the Moscone Center) - that sort of stuff is usually made out of wood pulp.

Paper isn’t necessarily known for being the most durable of materials at the best of times, but pulp magazines had a reputation for falling apart in your hands (especially if it’s raining). But this was acceptable to folks at the time, as being readily discardable in favor of the next publication from your favorite serial was part of the culture. As technology continued to advance and distributors could print newspapers almost as fast as articles could be written for them, the speed of production picked up. While it likely wouldn’t phase us modern twitter-users, at the time they were being released at a blistering speed.

As modern readers, we look back on pulp fiction as a deeply kitschy era of pop culture which would give way to comics as we know them today. But the truth is: pulp still exists - it’s just changed its form. Instead of hard-boiled detectives, we have fearless young children. Instead of vampires and zombies, we have animatronics, toys, and puppets. And instead of inexpensive paper: we have free-to-play and cheap indie game releases. But these spiritual elements are not all mascot horror inherited from its paper predecessor.

Pulp undeniably influenced the landscape of American fiction, however the genre was also associated with exploitation and the overall poor working conditions at the turn of the 20th century. Because when you have to make something return a profit? Well… you’re bound to cut a few ethical corners, right?

…Right?

Late-Stage Capitalism (We Live In Hell)

It is an unfortunate reality of being a game developer that our games - our precious babies that we have toiled away at making for years - have to be financially profitable. To see them as the art that they are is admirable, but the reality of the biz is that we need to turn a profit to keep the lights on (and the execs happy in their million-dollar houses).

This is an unfortunate, universal truth of game development, however there is something uniquely distinct about the “franchisability” of children’s horror properties of the modern era. Five Night’s at Freddy’s and Garten of Banban might have started as standalone, single-entry entities… but they have quickly exploded into entire franchises which have extensive spinoff material, merchandise, novels, and comics: turning a once-humble independent videogame into a fire-spitting hydra of capital.

And truthfully? It’s not a massive leap to understand how we got here. Children’s horror - mascot horror… it’s good money.

Here are some staggering figures I was able to find of recent mascot horror releases:

Five Nights at Freddy’s: Security Breach (Steel Wool Studios, Scottgames) - 2021: $44.5 million gross revenue, 1.4 million units

Poppy Playtime (MOB Games) - 2021: $2.1 million gross revenue, 1.5 million units

Bendy and the Dark Revival (Joey Drew Studios) - 2022: $5.5 million gross revenue, 237,000 units

…And people are taking notice. Studios are racing to create “the next FNaF” next to the original franchise itself as it continues to fight for relevance. Others want a cut of the ravenous market: not giving any care towards continuity (or even quality).

When the first Garten of Banban game was released for example, gamers across the internet found themselves asking: “is this for real?” It contained so many of the classic tendencies of the genre that a large portion of the player-base was questioning if it was a lampoon of the genre itself instead of a legitimate entry (if not a shameless cash-grab). It spawned more video-essays than you could possibly imagine in the weeks following its release.

As time has gone on, the jury is still out on how much (if any) of Garten’s design is tongue-in-cheek. But what was increasingly evident was how aggressive the series would be about trying to snatch a piece of the mascot horror zeitgeist. And I couldn’t help but feel all of this felt a little… Marvel-ish?

Michael Schulman of The New Yorker noted that “the Marvel phenomenon has yanked Hollywood into a franchise-drunk new era, in which intellectual property, more than star power or directorial vision, drives what gets made, with studios scrambling to cobble together their own fictional universes.” It doesn’t matter if it’s good. It doesn’t matter if this will have to become some sort of alternate timeline because things don’t match up. If it can hold the public eye and capture the imagination (like all good pulp can) - that’s good enough.

It is not enough to merely make a delightful game experience that a child can play with their friends. It’s not enough to create a few genuine scares, some laughs, and then allow the player to close the game when it’s time for dinner. All of that is a thing of the past. Now? Now games must become “IPs.” They must become “franchises.” The soul of a game and its story must be distilled and commodified into an asset which can then be turned into marketable plushies, comic books, children’s novellas, and now even Hollywood movies.

Welcome to indie horror in late-stage capitalism. I hate it here.

The Ethics of Mascot Horror

Now I would be remiss if I wasn’t to note that “ethics” don’t necessarily exist under capitalism blah blah blah - all that jazz. However, there are some serious questions that the current state of children’s mascot horror pose. How can these games be produced in their current iterations in an ethical way for their employees? Is it ethical to be marketing to children at all?

Unfortunately, in this fertile soil where everyone is trying to create the next hot FNaF-like, new studios are forming and attempting to bite off way more than they could chew… giving us some classic examples of what I like to call “developers behaving badly.”

For almost every single mascot horror game, there’s some sort of controversy regarding poor behavior on the part of the developers. We can sometimes chalk this up to inexperience with the ins and outs of making a game (which is already a gargantuan task in itself). Sometimes that’s reflected by the studio’s internal behavior, such as the reportedly horrific working conditions at Kindly Beast, the makers of the Bendy series, and the subsequent mass-firings.

Running a game studio is hard, but being a new studio in this incredibly fast-paced genre in an industry already synonymous with overwork and poor culture sounds awful. Without having the expertise of multiple shipped titles under your belt, the lack of knowledge about everything from development cycles to how to give proper feedback to your team becomes a massive hindrance to your success (critically, financially, and culturally). And if the issues with the genre were mostly internal, it would still be considered an issue by those working in the industry… but they aren’t.

There are instances of developers being out of touch with the needs and ideological stances of their players, such as the many controversies surrounding the FNaF franchise, but unfortunately the claims become worse, even still. Enchanted MOB, the developers behind Poppy Playtime have faced claims of everything from plagiarism, to bullying, and even dubiously sexualized depictions of underaged characters. …Then, of course, there was the backlash to their NFT project (this is a whole other topic, but to understand why these are controversial, please watch the YouTube documentary Line Goes Up), which was particularly outraging as it planned to lock story elements associated with the NFTs effectively behind an incredibly expensive paywall. Of course, the studio responded to each of these claims in turn, but it really seems like creators in this particular genre can’t seem to stay out of drama in their pursuit of the limelight.

Developers, are, of course, human, however I can’t help but feel a little yucky about the ethics of creating for, marketing to, engaging with, and receiving money from literal children. Pulp-y materials have always been popular with young people, however there is a specific element of greed simmering beneath the surface of these releases. Garten of Banban in particular fell under fire for this, as they quite literally included a merch button on the game’s menu at launch.

And you might be saying: hold on, Anna. What’s the big deal with marketing products directly to children? Turns out, there’s a whole field of ethics about marketing! An overview of decades of research regarding children and advertising from the International Journal of Advertising succinctly describes the concerns as such:

“The biggest concern is that children (up to 12 years old) are not yet capable of critically evaluating advertising. In comparison with adults, children are thought to be more vulnerable when confronted with advertising and, consequently, more susceptible to its effects. The rationale behind this assumption is that as children’s advertising literacy (i.e. understanding of and critical attitudes toward advertising) has yet to fully mature, they are less able to defend themselves against its persuasive appeal (Hudders et al. 2017; Rozendaal, Buijzen, et al. 2011). As a result, advertising targeting children is often perceived as unfair. These issues of fairness are even more severe in the contemporary media environment, which is characterized by subtle advertising formats that are integrated in entertainment (e.g. influencer marketing, advergames). Children have great difficulty recognizing the commercial nature of these practices (Hudders et al. 2017).”

This is because:

“…there are fewer identifiable commercial characteristics, and consequently children find it more difficult to recognize these forms of advertising. If children don’t recognize contemporary advertising messages as such, it is far more difficult for them to understand the commercial nature of those messages.”

- Rozendaal & Buijzen, Children’s vulnerability to advertising: an overview of four decades of research (1980s–2020s)

Therefore it follows that using video games to advertise merchandise to children featuring the “mascots” in question could be seen as morally dubious on the part of the developers. They could essentially be convincing children to buy things by exploiting their developmental inability to recognize that they are being advertised to. And sure, there is additional responsibility on the part of the parents or guardians of said child - but it doesn’t seem to be much to ask for the developers to stop taking advantage of the low advertising literacy levels of children. Come on, you guys.

Conclusion

I wish I had more concrete answers for many of the issues surrounding mascot horror and this new phase of pulp pop culture (apart from us desperately needing a union of course - that I’m very much serious about. Check out how a union in the games industry could benefit you!)

Unfortunately, the phenomenon of mascot horror is already at a full sprint, which means that we can only make guesses of how to improve the circumstances of the business and social practices within the genre, rather than trying to tackle the entire mascot horror industry at large.

Developers? Stop the bad behavior.

Now onto the business sense.

The FTC has established regulations when it comes to advertising to children, however they are mostly oriented towards television advertising, online privacy, and consumer protections. These relate to things such as how many advertisements can be shown during children’s television programming, that children should be able to access children’s content on a website (such as games or activities) without having to give any sort of identifying materials), and that there needs to be a statement on all direct sales saying that all purchases must be made by someone 18 years or older. But there’s very little regulation in terms of things like “advergames” - video games made by companies specifically for the purpose of advertising their products to consumers.

These types of games are not without scrutiny, and due to the “Get cool merch!” button being directly placed on the main menu of games like Garten of Banban, the world of mascot horror is veering rapidly toward this rocky slope. Advergames are nothing new, so by the time I was looking into them in 2023, academic debates about the ethics and even constitutionality of regulating advergames have already been raging in the minds of JStor users across the globe.

As you can see from the above example, many of the advergames that were created during the Flash-era of browser games were made by large food corporations. Because many of the foods being advertised were, for lack of a better term, “unhealthy,” there were multiple attempts to regulate advergames at a federal level in the United States. Unfortunately, because, once again, we are in the United States, lobbyists of the food industry made sure that these efforts would not be successful. It’s likely the precedent of those cases have paved the way for indie horror to teeter on the edge of going full mask-off advergame capitalism. But that doesn’t mean that future pushes for regulation can’t change things for the better.

We can hope that indie horror creators are truly in it for the art. That they, like me, genuinely love horror games. That they honestly love making spooky content for kids. That they are fostering healthy work environments and inspiring the next generation of game developers. Maybe they will see the error of their ways when it comes to the blatant cash-grabs, or maybe the FTC will change its mind about increasing regulations regarding advertising in gaming. Maybe in a few years we will look back fondly on the mascot horror era of indie horror as a quirky little experiment and a fun trend. Maybe developers will take notice of all of the poor behavior on the part of their peers and hold themselves to a higher standard.

Maybe.

…But it sure sounds like wishful thinking to me.

Thank you for reading another installment of Resident Anna. As an indie-horror (and even mascot horror fan) myself, I’ve been wanting to write about this topic for quite some time. I hope that this has given you some food for thought and you’re able to take a closer look at the next Five Garten’s at Bendy and the Tattletail or whatever whenever the next installment releases next tomorrow. But for now? Farewell.

Great read! I did a piece on the same topic over on my Medium after watching some video essays on the topic, but more so just about my distaste on mascot horror. I think the comparison to pulp is super interesting! I hadn't seen anyone make that comparison, and I totally see it!