The Time a Queer Horror Game Started a Moral Panic

On the peculiar history of cult-hit Rule of Rose, moral panics, and what it might tell us about our current climate

Content Warnings: This article contains discussion of moral panics, trauma and traumatic memories (especially concerning childhood), child abuse (physical and sexual), violence towards animals, abusive power structures, mass-murder, death of children, sexualization of underaged characters, self-harm, suicide, and anti-LGBT bigotry.

I know that’s a lot - I keep it deliberately high-level and nondescript on many of these things: and some of the listed content warnings are because Rule of Rose was accused of having alarming content that (spoiler alert) wasn’t actually in the game - but I wanted to include them here just in case.

And, of course, spoilers for Rule of Rose (2006).

Overview

On On March 7, 2007, members of the European Parliament gathered in Strasbourg, France, to discuss a very pressing issue facing the children of Europe. Something so dangerous, so alarming, that they proposed the creation of an entirely new body within Parliament itself: the “European Observatory on Childhood and Minors.” And what was all of this hubub about? What could possibly have motivated them to expend such resources and demand additional oversight?

…A single video game from Japan.

If you’re a horror fan, you’re likely familiar with Rule of Rose’s legendary status. The game hadn’t even shipped when it began to make serious waves, particularly throughout Europe and Oceania. To this day, copies run anywhere from $150-$500 on sites like eBay, as disks are hard to come by after the game’s heavily restricted launch. To this day, your best bet at experiencing the game comes from a cracked copy played on a PS2 emulator (or merely watching a playthrough on YouTube from one of the lucky ones with a copy).

But something about the incorporeal nature of this game only adds to its mystique: so what is the big deal about Rule of Rose? Why was it banned in so many countries? And what might its history be able to tell us about the political climate we’re in today?

Well, folks: grab yourself a red crayon and let’s dive in.

What is a Moral Panic?

Before we are able to comprehend the unique history of Rule of Rose, we first must understand the psychology and sociology of the phenomenon known as a “moral panic.” Though you may not have heard the phrase before, if you are a person living in the United States in the past few years, you are intimately familiar with the concept.

Popularized in Cohen’s study of youthful hooliganism in post-war Britain, ‘moral panic’ constitutes a keyword in social-scientific studies of crime, deviance, and control. Referring to episodes where folk devils – moral outlaws and ‘visible reminders of what we should not be’ – are blamed for societal malaise, the term captures how ‘right-thinking’ actors transmute deviant outsiders into potent sources of anxious indignation. …For Cohen and his peers, panics represented media events, with journalists and broadcasters playing an essential role in identifying aberrant behaviour and mobilizing consensus and concern.

- James P. Walsh, “Social Media and Moral Panics” from the International Journal of Cultural Studies

Sound familiar?

Here in America, we love moral panics. We have one every 5-10 years or we start gnawing on our furniture like a dog without proper enrichment. From the Salem Witch Trials to the Satanic Panic of the 1980s and 90s, we love to pretend the end of society is nigh.

It’s important to note that moral panics are distinct from the phenomenon of “mass hysteria” - or known by its proper name: mass psychogenic illness (MPI). MPI is a psychological phenomenon wherein there is an apparent transmission of symptoms or behaviors, rather than a sociological phenomena. Examples of MPI include the Dancing Plague of 1518 or the 2011 incident in Le Roy, New York. The phrase “mass hysteria” is commonly used colloquially in an interchangeable manner with “moral panic,” but for the purposes of this article, I will only be addressing moral panics and referring to them as such.

Moral panics are often concerned with some sort of vague idea about moral corruption or a degradation of “traditional values” and “morality” (whatever that might mean). As nondescript as these concepts are on the surface, they are very compelling in terms of rhetoric and psychology. Therefore, moral panics tend to follow a typical pattern as outlined by Stanley Cohen - the sociologist who coined the term in the 1970s.

That last paragraph is also very important: it does not matter if the subject of the moral panic is in any way new or original - it can be a thing or concept which has existed for centuries, or something that was invented yesterday. The thing that makes it a target is that the genuine populace (often, as Cohen noted, encouraged by the media) has decided that it is the manifestation of often completely unrelated social anxieties.

That’s because moral panics have little to do with the actual threats a population may be facing - they are primarily concerned with social control. Moral panics historically have occurred during times of great societal change and anxiety, such as shifting social dynamics, war, or technological advancements. As Scott A. Bonn, PhD writes for Psychology Today, moral panics are about maintaining the status quo - and thus often prey upon misconceptions, stereotypes, and biases about minority groups that are often already present within the population. This creates what is known as a “folk-devil.” Essentially: an urban legend of a societal problem.

Bonn also notes that the creation of these folk devils creates a mutually-beneficial arrangement for politicians, the police, news/mass media, and social media as they enter a feedback loop. This continues until they have whipped up the public into a frenzy and a full-blown moral panic is achieved. It is at this point that we see “the passing of legislation that is highly punitive, unnecessary, and serves to justify the agendas of those in positions of power and authority.”

Moral panics aren’t about the actual problems that plague a community. They aren’t about caring for the actual health and safety of your fellow man. They aren’t altruistic in the slightest: moral panics are strictly about social control. And while that often manifests in “punching down” on already underserved groups of people, sometimes the subject of a moral panic is… honestly just bizarre.

Things which have been the subject of moral panics:

Communism - the famous “Red Scare” of the 1950s.

Jazz/rock and roll/blues - the “Devil’s music” - or, racism: repackaged. See also: metal in conjunction with the “Satanic Panic”

Witchcraft (this one is a member of Moral Panic: Greatest Hits!)

Dungeons and Dragons (for some reason)

Islamic Extremism and terrorism

Video games - particularly in relation to depictions of violence

Immigration - or, racism: repackaged (again).

The so-called “War on Drugs” - see also: marijuana, crack, and opioids/fentanyl

“Satanic Ritual Abuse” often in conjunction with pedophilia, which is a tangential repackaging of the ancient anti-Semitic conspiracy theory of the “blood libel.” See also: the phenomenon of “repressed memories,” and the “Satanic Panic.”

The LGBT+ community - see also: the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the “Lavender Scare” of the 20th Century, and the “grooming” conspiracy theory.

Human trafficking (especially that of children) - see also: the QAnon conspiracy theory and… sex work in general.

And you might ask yourself: which one of these does Rule of Rose fall under? Well, perhaps the reason why Rule of Rose ignited a moral panic is that it ticks most of the above’s boxes, all wrapped up into a nice, neat package. Or, at least, you may think it ticks all of the above boxes if you don’t actually know what the game is about or to whom it is actually being marketed (or know much about video games in general).

Essentially, it was a a supreme folk-devil. Rule of Rose is a video game with violence and frightening imagery that was made in a foreign country and features LGBT themes, the concept of repressed memories, and even discussions of child abuse and adolescent sexuality. Despite being rated M here in the States, most of the characters are minors, creating the perception that it was aimed at/marketed towards and therefore a danger to children.

So. You know. Everyone was going to be so normal about it.

Misconceptions Embroiled the Launch

In a chapter about Rule of Rose in Moral Panics in the Contemporary World (2013), scholars Elisabeth Staksrud and Jørgen Kirksæther noted that the media panic appeared to move in a series of stages: all of them very silly, yet unfortunately leaving a lasting mark on regulatory processes (and the legacy of the game itself).

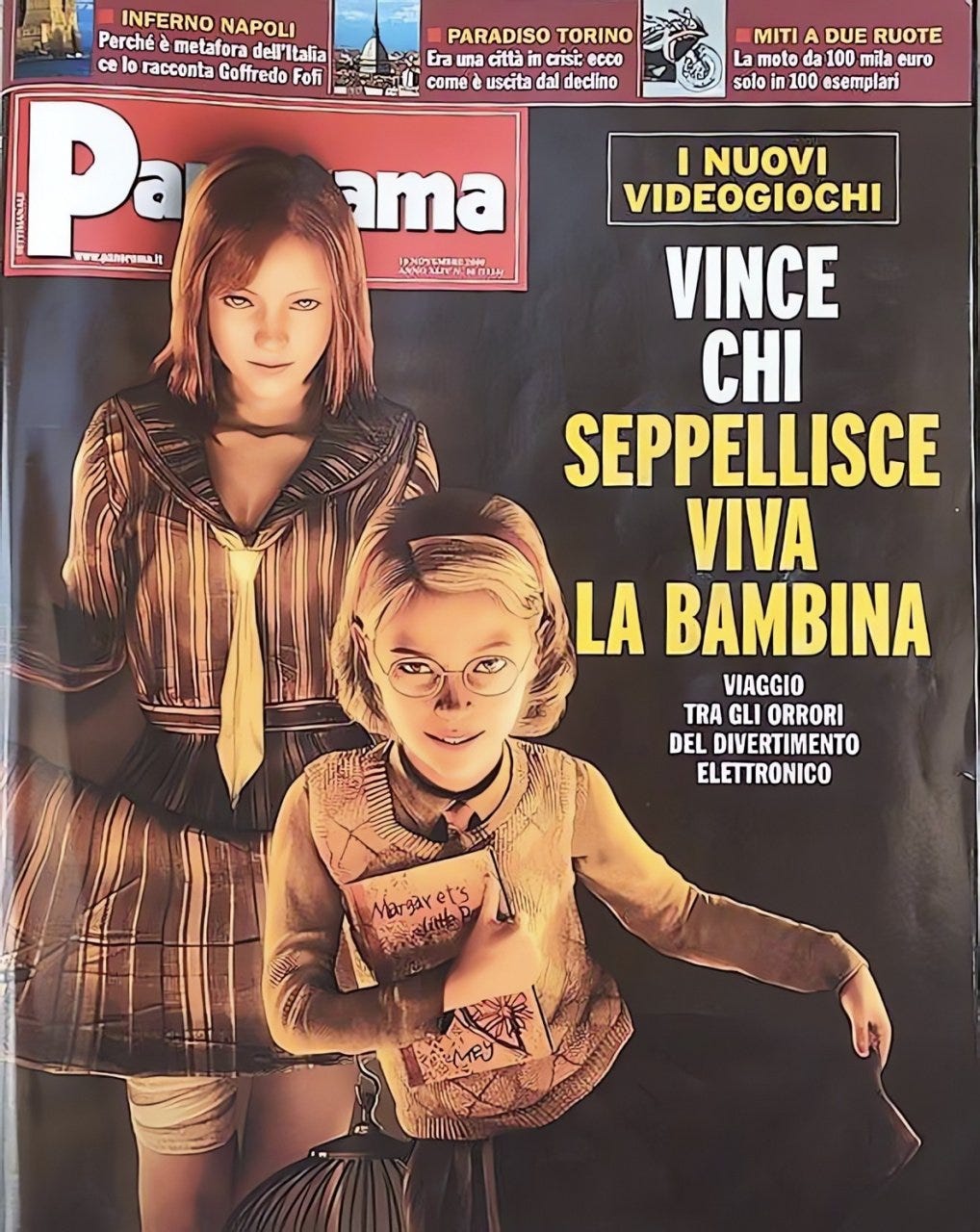

It all starts with a news article. On November 10th, 2006, the Italian news publication Panorama made their cover story about Rule of Rose. It bore the provocative title: “Vince Chi Seppellisce Viva La Bambina” - translating to: “he who buries the little girl wins” (bold to assume your player is a man or uses he/him pronouns, but I digress).

The article within, which may actually have been plagiarized according to some web sleuths, scathingly detailed that the game (and medium in general) contained violent, sexual content concerning underage girls. “Every single frame is dripping with perversion… Every scene features homoerotic and sadistic subtext,” declared the author.

This condemning quote is speculated to be referring to the prerendered footage shown in the trailer - some of which isn’t present in the game at all. And the title, which refers to “burying a little girl,” likely is referring to the cutscene toward the beginning of the game where Jennifer falls into an open grave. This, of course, is symbolic when seen in context - no one does any actual burying of any children within the game. But they didn’t let that stop them.

In fact, as Staksrud and Kirksæther note, they don’t let much stop them at all.

“The Panorama feature includes an interview with Italy’s president of the Committe for Childhood, Anna Serafini. Serafini, admitting that she does not know how to even switch on a PlayStation, is terrified by the described content of the game and questions how it could have reached the market. The same reaction comes from Rome’s mayor Walter Veltroni, calling for a national ban of the game.”

- Staksrud & Jørgen Kirksæther (2013)

Franco Frattini (the European commissioner for justice, fundamental rights, and citizenship at the time) subsequently called an immediate meeting for all ministers of domestic affairs within the EU. From there, the moral panic spread throughout Europe, namely to the UK, with the primary narrative becoming: “this is dangerous for the children!”

It is worth noting that Rule of Rose was never intended for a child audience, and the associated ratings reflected this intent. In Japan, which uses the CERO rating system, it was rated a C, meaning that it was only suitable for players ages 15+. In the United States, it was given an ESRB rating of M (17+). And even in Europe, it was given a PEGI rating of 16+. This, however, did not satisfy the European Parliament. The previously-established ratings systems built for this exact purpose were no longer adequate to protect against the moral threat of video games. Frattini said that they would need a complete overhaul if there was ever a chance to prevent this kind of “sadistic,” “perverted” content from reaching the impressionable children of Europe.

In an interview with British trade outlet MCV, Lori Hall, the secretary of the British Video Standards Council - the arbiters of the PEGI rating system - was outraged by Frattini’s suggestion that the PEGI system was inadequate or that they had been careless with their determined rating for Rule of Rose.

“There isn’t any underage eroticism,” added Hall. “And the most violent scene does indeed see one of the young girls scare Jennifer with a rat on a stick. But the rat’s actually quite placid towards her and even licks her face.”

“I wouldn’t call the game violent. We’re not worried about our integrity being called into question, because Mr. Frattini’s quotes are nonsense.”- MCV Article “505 Pulls Rule of Rose Release” from the Wayback Machine

All of this based on hearsay about the content of the game. I can’t help but wonder if the English adage of “you can’t judge a book by its cover” has a similar version in Italian.

The Reality: What the Game Was (And Wasn’t)

You’ll notice we got terrifyingly far into this article without even discussing the game itself - it’s so so easy to get wrapped up in the controversy and sensationalist headlines, you might forget to ask: …what’s the game about anyway?

And let me be frank: this game is weird - but not in the ways the moral panic thought it was.

In Rule of Rose, you play as Jennifer: a 19 year-old English woman in the 1930s grappling with her traumatic past. Now an adult, Jennifer find herself returning to a dilapidated orphanage (that is also an airship - we’ll come back to this) for reasons unknown. In an “the inmates are running the asylum” arrangement, the remaining children run the orphanage with the iron fist of beaurocracy: The Red Crayon Aristocrat Club.

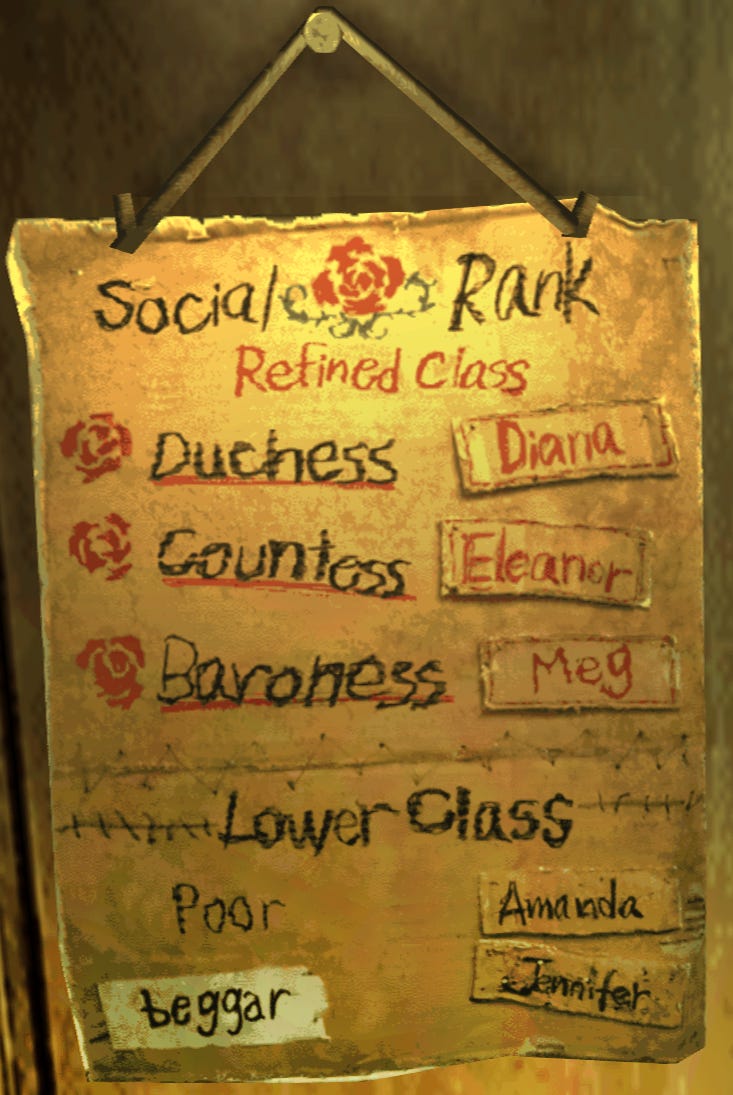

With few adults left to care for the children, the Aristocrats each have their rank and function within the organization to create a semblance of order. In a fashion that emulates how children might interpret classism in 1930s Britain, this manifests as having class-ranks, particularly: the Refined Class (a few named individuals), the Bourgeoisie (other orphans in decent standing), and… the lower class. Guess which one Jennifer’s in.

At the topmost tier of this hierarchy, although not written on the above sign, is the Prince and Princess of the Rose. All orders come from them. Now, this childlike attempt at creating a social hierarchy might have truly been made maladaptively in order to create structure in the absence of adult supervision - a feat which honestly might be commendable given the circumstances.

…But these might be some of the most messed-up kids on the planet.

Meet the Aristocrats

In order to explain what the heck is going on in this story, you’ll need to meet the decently large cast. This is by far not all of the members of the orphanage, but these are the characters we interact with the most.

Diana, the Duchess:

Diana is the oldest of the orphans at the orphanage - appearing to be in her mid-teens (I’d wager about 14 or 15 if I had to guess). It can be assumed that her age is partially why she is ranked so highly in the Aristocrat Club, and can thus “command anyone below her” as dictated by the rules. In the absence of proper adult supervision, she might be the best they’ve got!

Diana is the most outwardly violent of the girls, showing multiple traits consistent with sociopathy: with a low-conscientiousness for others and even being depicted harming animals, she is almost always looking for the first opportunity to cause harm to someone else.

As we continue throughout the story, it’s alluded to that she is being sexually abused by Mr. Hoffman, the headmaster of the place - and it is likely she is not the only one. We can assume that her aggression toward the others is an attempt to feel in control and safe in her own way: by subjugating others, she is attempting to soothe her own pain from victimization.

Eleanor, the Countess:

Eleanor is a younger member of the Red Crayon Aristocrats (I’d guess perhaps 9 or 10 or so). She does not talk much, and is quite introverted and aloof - she rarely ever appears to be looking directly at whoever she is speaking to. She participates in the Aristocrat Club, though it does not appear that she revels in the cruelty of the punishments - it is unclear how much she enjoys any of it, and I wonder if she’s perhaps just “going along to get along.”

Eleanor is most fond of her pet bird, and is often associated with bird imagery, as she wished she might "sprout wings like a bird and fly away to wherever she pleased." We get the sense that she would rather be anywhere but here (and honestly I wouldn’t blame her).

Some in the fanbase believe Eleanor may be autistic (or otherwise not neurotypical). She does appear to have low verbal communication skills compared to the others, and birds may serve as a comfort object and special interest. This has never been commented on by the developers, but many in the fanbase have felt “seen” in this aspect by Eleanor’s character.

Meg, the Baroness:

Meg is the final member of the Refined Class of the Aristocrats with the title of Baroness (and I’d guess she’s around 11 or 12). Though she is the lowest tier within her rank, she appears to have the important duty of functioning as secretary for the Club. The book she always carries around with her contains all of the rules (and the associated punishments for breaking them) and direct messages given to her from the Princess of the Red Rose.

Meg is a dangerous combination of arrogant and highly intelligent, and uses her wits to dream up new methods of punishment for any who dare violate the rules. This gives her almost a mad-scientist vibe, and cements her as the “mastermind” of the group. She then turns to Diana to act as the “enforcer.”

Oh - another thing about Diana. Meg has a mega crush on her. This is revealed over the course of the game when Jennifer finds both halves of a torn-up love letter. Meg is humiliated, and takes it out on Jennifer by shoving her in a bag. These kids are very well-adjusted, to be sure.

Amanda, the Poor (then Miserable)

Joining Jennifer in the “Lower Class” is Amanda, who I would guess is 10 years old or so. She is quite self-conscious and insecure in personality, likely from living under the hard rule of the Red Crayon Aristocrat Club for so long. She clearly longs to be like the members of the Refined Class, but due to beauty standards or social convention… she just can’t swing it. And the Refined Class girls are determined to make sure she stays at the bottom of the heap.

At first, Amanda welcomes Jennifer as her fellow member of the proletariat. But after Jennifer is promoted from Beggar to Poor (and Amanda is thus demoted, becoming “Miserable”), Amanda becomes jealous and vindictive. Her desire to climb socially and gain social approval appears to come before all else, and she isn’t concerned about who she needs to step on or destroy in order to do it.

However, later in the game, she apologizes to Jennifer for how poorly she treated her following her “demotion.” How much remorse she genuinely feels for this is questionable, given how quickly she was willing to abandon her principals in order to gain approval from the rest of the Aristocrats.

The Rules

…Boy do the Aristocrats drive a hard rule. As someone who attended an all-girls’ middle school, Rule of Rose is terrifyingly real in depicting how unforgiving social structures are in young girls. As young women (already pitted against each other due to patriarchal conventions of society) seek a sense of understanding in their own identities and where they might stand within a community - they are just freaking mean.

The Aristocrat Club dictates a series of intricate rules and rituals as determined by the Prince and Princess. Failure to follow these decrees will result in punishment (there is something very ominous about a cute, British child saying: “I’ll kill you :)” in a way that you can tell they very much mean it).

The general ruleset is as follows:

Anyone who disobeys any of the Rules of the Rose are to suffer dire consequences and terrible penalties. Most of these punishments are invented and performed by the Baroness, Meg.

The Aristocracy must always follow the instructions of the Prince and Princess of the Rose, and all rules, regulations, and information from the Prince and Princess of Rose are to be read by the Baroness.

The Duchess, Diana is allowed to command anyone below her.

The Prince and Princess want a gift every month: those who do not give them a gift are to be punished by the Baroness' choosing.

There are severe penalties for those who do not obey the rules.

If anyone of the Aristocracy disobeys the Prince or the Princess of the Rose, they will be punished by Stray Dog - an enigmatic figure who we will meet later.

What ensues is a bit of an obtuse story (narrated as if in a children’s book) about grappling with childhood trauma, emerging sexuality in adolescence, and just how mean young girls can be in social settings.

“We wanted to depict the darker side of children. Not really dark, per se, but if you really think about kids, they aren’t really afraid of the same things that adults are, and often aren’t aware of the consequences. Something that may seem benign to them may seem wrong or frightening to adults, but it’s really just a form of innocence.”

Much of the gameplay focuses on exploring the orphanage-turned-airship, finding the associated “gifts” for the Aristocrat Club, and exploring fractured memories of Jennifer’s past. Combat is relatively scarce, culminating in a few actual boss fights but mostly just hoards of creepy childlike imp things.

The Actual Plot of the Game

In truth, the game is allegorical: the first scene of the game involves an adult Jennifer appearing to doze off on a park bench, insinuating that the entire events of the game may be her repressed memories attempting to manifest. There’s also a very real reason why the orphanage inexplicably moonlights as an airship.

Jennifer was involved in a horrific crash of a luxury airship in 1929 in the English countryside - killing everyone onboard, including her parents… except for her. Before the wreckage could be searched by authorities, a local farmer came on the scene, and found only Jennifer left alive. This farmer (like everyone else in this story) was mentally unstable. This is a result of the loss of his only son, Joshua, to illness.

In a moment of what can only be described as a grief-fueled psychosis, Farmer Wilson (known by the Aristocrat Club as “Stray Dog”) believes Jennifer to be his son Joshua. He kidnaps her and holds her hostage in his son’s old bedroom: cutting her hair and dressing her as a boy.

It is during this tenure that Wendy (the Princess of the Red Rose), one of the girls from the orphanage, spotted Jennifer through the window of Mr. Wilson’s home. The two began exchanging letters, and eventually fell in love (or, at least, what middle schoolers might deem love).

Wendy said that she would help “Joshua” escape the terrible man holding her hostage, and take her to the orphanage where she actually belongs. All she needs to do is swear her everlasting love for her. Which she does. Saying:

Everlasting true love, I am yours.

One night, Wendy helps Jennifer escape and brings her to the orphanage, where she is welcomed. The trouble comes about when Jennifer finds a homeless puppy, which she names Brown. She loves and dotes on her little doggy friend so much, that Wendy becomes jealous, and schemes with the other girls at the orphanage to kill Jennifer’s dog in a jealous rage.

Jennifer, of course, is apoplectic and swears to never forgive them. The rest of the girls say it was Wendy’s idea, and want to promote Jennifer to being the “leader” of their group in a mea culpa. Furious at her “demotion,” Wendy goes back to Mr. Gregory’s house to manipulate him to come visit the orphanage.

When he does… he goes on a rampage, killing all of the girls except for Jennifer in an act of mass violence. When he comes to his senses moments later, he ends up taking his own life. When the police show up, finding the entire population of the orphanage deceased except for Jennifer, the truth comes out about her identity as the sole survivor of the airship, too. There is a media frenzy about the sensational story… and then the trail goes cold from there.

We can assume Jennifer has survived into adulthood, but not without heavily repressing her memories through dissociative amnesia. As they come spilling out over the events of the game, we can see how each of the individual Club members might be embellished versions of real girls at the orphanage - just dialed-up to 11 and distorted through a childlike lens.

And like, okay, that’s pretty weird. But where did the misconceptions about the moral panic come from?

Themes Driving Misconceptions

Adolescent Sexuality

Rule of Rose is definitely a queer game. From our 2023 perspective, a video game involving the queer development of an adolescent protagonist is demonstrably mainstream: see Ellie from The Last of Us or Max from Life is Strange. In Rule of Rose you have two sapphic relationships between characters anywhere from ages 10-15.

While I was not able to find any definitive data due to the subjectivity of the experience, a cursory glance on the internet indicates that people who experience romantic and/or sexual attraction often become aware of those attractions around ages 10-13. A study from the American Psychological Association’s journal of Developmental Psychology seemed to confirm this, adding additional clarity on the conventions of these early romantic connections.

“the development of early romantic relationships follows a phase-based approach, whereby adolescents begin with fairly short-term, shallow romantic connections primarily occurring in peer groups”

Therefore, Jennifer’s childhood puppylove for Wendy would be considered developmentally appropriate for their age. It’s about as squeaky-clean as you could get in terms of adolescent romance: it’s quite literally modeled after the standard fairytale trope of a prince and princess living happily ever after. The only kisses we see exchanged are that of a peck on the forehead and cheek. And while they might have pledged their “everlasting” love for each other, it’s undeniable that these kinds of relationships can’t be anything other than shallow. This is also the case with the relationship between Meg and Diana, which is slightly more mature based on their more advanced ages, but is still centered around someone writing a frilly love note in crayon (and her love ultimately going unrequited).

One of the major concerns referenced above was that it contained “erotic” content associated with children. And while there is definitely a few moments that I think were meant to be shocking to adults (such as a moment where Diana puts Meg’s cut finger in her mouth to stop the bleeding in a way that’s definitely suspicious), I think this is likely overstated. I can’t help but feel that this inherent discussion of sexualization is a remnant of fearmongered attitudes toward the LGBT community. The idea that something being queer is inherently sexual is incorrect, and is rhetoric that has fueled moral panics concerning the LGBT community and how their presence is somehow a danger to children for decades.

It is not “dangerous” to merely depict to young LGBT characters experiencing their first crushes. It would not be so even if the product in question was marketed to children, but given that this game was clearly made and marketed for adults, this element of concern is superfluous. Coming-of-age stories often tell of first romances in the tweens: the genders of the parties involved should be of no consequence.

Common concerns about sexual depictions of children often settle on Diana, who is certainly the oldest of the group. Apart from the one “finger in the mouth” moment, one of the pieces of evidence used to declare Rule of Rose as sexualizing children comes from Diana’s curtsey.

Her curtsey is indeed quite high, showing off quite a bit of her legs (while I couldn’t find an exact citation for this, this supposedly was declared “lifting up her skirt” in the European Parliament). However, most fans of the game insist that this is done to to highlight the bandage around one thigh - which some people believe may be hinting at self-harm. Self-harm is never explicitly stated with Diana, but is with a peripheral member of the orphanage (Clara), so its presence within the lexicon of the narrative definitely makes this bandage suspicious. Additionally, the combination of her high curtsey and her low-cut neckline could be subtle cues to how she is quite precocious sexually for her age, which is unfortunately consistent with children who experience sexual abuse.

Other concerns with eroticism appeared to be concerning the returning motifs of ropes and punishment, which could evoke… certain adult activities. However, in the game, the symbolism of the ropes is often coupled with a character or character(s) being in a position where they are thematically helpless. The theme of punishment for being in violation of a social contract may also be reminiscent of Jennifer’s history of abuse and post-traumatic stress, combined with the strict social rules maintained by girls in this developmental chapter of their lives.

It’s generally agreed upon by modern horror fans that while the concerns of the moral panic look very alarming on paper, actually playing the game makes these various claims deteriorate rather quickly. It’s almost like those people in the Italian parliament should have played the dang thing.

Violence - Particularly Towards Animals

Depictions of violence in video games has been the subject of moral panics for decades, but top academics in this area have found that video games do not inspire or otherwise influence violent tendencies in the player.

Now, that is to say, there are quite a few depictions of violence towards animals in Rule of Rose - and for the purposes of this article, I will not be providing any screenshots associated with it.

It is common knowledge that seeing a child exhibit any kind of harm towards an animal is a red flag, as it could indicate that the child struggles with empathy. You may have colloquially heard that abuse towards animals in childhood is an indicator or predictor of sociopathy, or that a child may become a serial killer. Like many other soundbites of pop-psychology: the reality is a bit more complicated than that.

The inclusion of children committing violence towards animals appears to be an intentional addition to Rule of Rose, as it’s frequently noted that “children who abuse animals have either witnessed or experienced abuse themselves.” And in Rule of Rose, it is very obvious that there is abuse occurring at the orphanage - likely both of a physical and sexual nature. Showing just how careless the members of The Red Crayon Aristocrat Club are towards animals could indicate the degree to which they were impacted by such abuse, or otherwise is meant to serve as an indicator of how their capacity for empathy has just completely gone down the drain.

Of all of the moral panic concerns about this game, I think this one actually holds the most water - and yet, it seemed to get the least amount of focus as it’s not quite as sensational. Funny how that works.

What Can This Tell Us About Today?

You may be like me: in researching for this article, I had multiple moments of deja vu. So many of the sources I found and historical news coverage I retrieved felt like they could have come out last year. Concerns for the “welfare of the children”? Concerns about LGBT “grooming”?

Because the truth is: we are in a moral panic today in America. Multiple overlapping ones, even. Between the rise of far-right anti-LGBT content creators and think tanks like L*bs of Tiktok and The D*ily Wire, we’re seeing the emergence of anti-LGBT “grooming” conspiracies. These specifically center around people who are of transgender experience and/or those who do not otherwise fit the conventional “respectability politics” of the 21st century. And chances are if you’re reading this - you don’t need me to tell you.

When you’re seeing a moral panic unfold in real time, it’s almost like being Jennifer tied to that support beam: only allowed to listen as a member of the Aristocrat Club tells you how things are going to go down. It’s easy to feel helpless and scared, especially if you are someone who is directly impacted by these feigned “concerns.”

What we can do is be prepared.

The thing about moral panics is that they have a distinct playbook. Watch for the signs. Don’t fall for it. Stand up for those impacted. Look out for each other. Because unfortunately, just as chaotic times will always come and go: that means moral panics will, too. Only, we will be vigilant. No one’s getting buried on our watch.

Thanks for reading another installment of Resident Anna. The history surrounding Rule of Rose has always fascinated me, especially in a sociological sense.

What I said in that last part is very real. If you want to learn more about the recent anti-LGBT moral panic and its associated legislature (and what you might be able to do to help), check out the ALCU’s page about LGBT+ Rights, and the Transgender Law Center.

You are not alone. We will fight for and with you.

I would like to give a special thanks in this article to Elisabeth Staksrud, faculty at the University of Oslo, for sharing her and her colleague’s research with me as I worked on this article!

Staksrud, E., & Kirksæther, J. (2013). 'He who buries the little girl wins!' - Moral panics as double jeopardy. The Case of Rule of Rose. In Moral Panics in the Contemporary World (pp. 289). Bloomsbury Academic

Thanks for reading!

![According to Cohen, there are five sequential stages in the construction of a moral panic:[1][7][22] An event, condition, episode, person, or group of persons is perceived and defined as a threat to societal values, safety, and interests. The nature of these apparent threats are amplified by the mass media, who present the supposed threat through simplistic, symbolic rhetoric. Such portrayals appeal to public prejudices, creating an evil in need of social control (folk devils) and victims (the moral majority). A sense of social anxiety and concern among the public is aroused through these symbolic representations of the threat. The gatekeepers of morality – editors, religious leaders, politicians, and other "moral"-thinking people – respond to the threat, with socially-accredited experts pronouncing their diagnoses and solutions to the "threat". This includes new laws or policies. The condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible. Cohen observed further:[28] Sometimes the object of the panic is quite novel and at other times it is something which has been in existence long enough, but suddenly appears in the limelight. Sometimes the panic passes over and is forgotten, except in folk-lore and collective memory; at other times it has more serious and long-lasting repercussions and might produce such changes as those in legal and social policy or even in the way the society conceives itself. According to Cohen, there are five sequential stages in the construction of a moral panic:[1][7][22] An event, condition, episode, person, or group of persons is perceived and defined as a threat to societal values, safety, and interests. The nature of these apparent threats are amplified by the mass media, who present the supposed threat through simplistic, symbolic rhetoric. Such portrayals appeal to public prejudices, creating an evil in need of social control (folk devils) and victims (the moral majority). A sense of social anxiety and concern among the public is aroused through these symbolic representations of the threat. The gatekeepers of morality – editors, religious leaders, politicians, and other "moral"-thinking people – respond to the threat, with socially-accredited experts pronouncing their diagnoses and solutions to the "threat". This includes new laws or policies. The condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible. Cohen observed further:[28] Sometimes the object of the panic is quite novel and at other times it is something which has been in existence long enough, but suddenly appears in the limelight. Sometimes the panic passes over and is forgotten, except in folk-lore and collective memory; at other times it has more serious and long-lasting repercussions and might produce such changes as those in legal and social policy or even in the way the society conceives itself.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!iBeM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F279a3404-7c32-4874-8c8a-3f7ab6377cc5_1375x554.png)

Love this deep dive and explaining the actual game vs the insanity that blew up before it was really even shipped out. It's such a wonderfully done game too (minus the combat, oh my god) - and when I was younger I was so blessed to have a copy.

It's also wild to me that the Silent Hill games didn't get more negative press as well, or Fatal Frame. For any reason. The news is so quick to illicit panic over horror games, especially when they have even a single iota of real life trauma or issues shown

Wow, I'd never heard of this game before! Thanks for doing a deep dive around it, that was so fascinating. It always freaks me out a little seeing the repetitive telltale signs of moral panics flaring up across different points in history.